[For the background on this series, please see the Introduction first]

Did you know they’re tracking your every click?

You probably did.

Do you know how and why they do it?

The secret is the link.

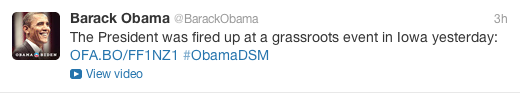

Follow Obama on Twitter or Facebook, and you will see a steady stream of postings with quotes, information about events, and statements of policy. And because of the 140-character brevity of Twitter, most of these tweets are just teasers with hyperlinks that lead to further discussion, photos, or videos. Like this one:

You can tell it’s a video, obviously, but the URL looks strange: OFA.BO/FF1NZ1. It’s clearly not YouTube or Vimeo or any other well known video web site. But when you click the link, you find yourself nonetheless at YouTube:

How’d you get there? That’s mystery #1…

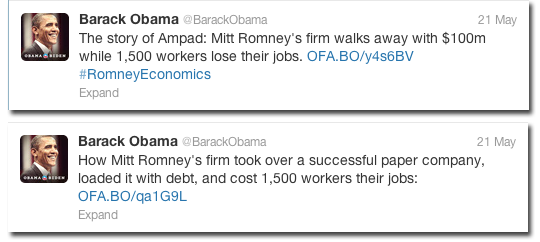

But the plot gets thicker when later on you notice a pair of similar Obama tweets:

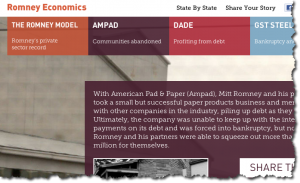

Both tweets are on the same subject and if you click either link you will be taken to the same anti-Romney page:

But look closely at the two tweets again: each tweet has a different OFA.BO URL. Why? That’s mystery #2…

Fortunately, the answers to these mysteries are fairly straightforward.

With mystery #1, as you no doubt suspect, the Obama campaign is using a custom URL shortener (for more details on URL shorteners, see this article). You’re probably familiar with more popular URL shorteners like bitly and TinyURL. The Obama campaign is using one of these services (see Asides at the end), but working with their own private domain, OFA.BO.

When you click on the link http://OFA.BO/FF1NZ1, the OFA.BO URL shortener (which is just a specialized web site) “unshortens” FF1NZ1 and tells your browser the actual web site you need to visit is at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uoEY1W2Fqxs. Of course, your browser hides this two-step process from you. Instead, it quickly takes you to the YouTube page – so quickly that you don’t notice the stop at OFA.BO. It gives the illusion that if you click on the link in Twitter you’ll go right to YouTube

But while you were going through OFA.BO, your click is captured by the Obama campaign: they know which specific tweet caught your eye and got you to click on the video. Very tricky!

The motivation for doing this is pretty simple. Like any marketer, the Obama campaign wants to know what works and what doesn’t. A tweet that gets very few clicks is a failure and won’t be repeated or imitated. But a tweet that gets an enormous amount of clicks is a success and will be used as a model for future tweets.

This is especially useful for them when the campaign is trying to figure out how to phrase or explain something. That’s the solution to mystery #2, where the two similar tweets have different shortened URLs: the Obama campaign wants to know which of the two messages gets the the biggest reaction, and so it tracks each tweet by giving it a different URL. Is it the tweet focusing on Bain’s profit at the expense of jobs? Or is it the other focusing on what sounds like mismanagement? By the time you’re reading this, the Obama campaign has undoubtedly recorded enough clicks to know if either or both gets people fired up.

The value of this analysis extends well beyond Twitter: as messages are tested on Twitter and the best phrasing discovered, the campaign knows better how to present Obama’s messages in person and in traditional media. If you hear Obama speak on the subject, and he focuses on how much money Bain made from Ampad, you know the first one got all the clicks. You can almost imagine them using Twitter not for Twitter’s sake, but to research how to put an important speech together!

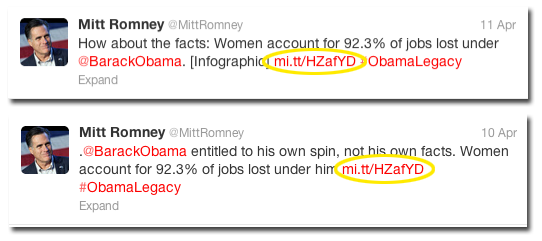

Of course Mitt Romney’s team has its own URL shortener: MI.TT. They too can track clicks. Interestingly, they haven’t figured how to test multiple tweets to hone a message. That’s probably because they don’t tweet anywhere near as often as Obama does right now, and multiple tweets on the same subject are rare for them. But in the times they do, the campaign doesn’t use unique codes:

Granted, there isn’t much difference between these two tweets, but Romney’s team has no way of knowing which of the two is more popular. You snooze, you lose… Politics, like football, can be a game of inches.

There are some key take-aways from this first Twitter Secret of the Obama Campaign:

- Always use a URL shortener for links you post on Twitter (or Facebook). Make sure the link shortener has a convenient way of producing reports on people’s clicks.

- Try out different forms of your messages, and pay attention to which one(s) work the best. It’s more effort, but you’ll be rewarded with a better knowledge of what succeeds on Twitter (and perhaps beyond).

For some of you, this secret seems like it is just common sense. And if it does, I apologize. But I’m always amazed by the number of people who don’t use anything but the most primitive tools for using Twitter. As an example, in this analysis I did of what Twitter tools US Senators use, over 50% of their usage is via the web interface at Twitter’s homepage. As a result, they have no way of knowing whether people are responding to their tweets or not. And these are politicians with jobs of national importance — and who only keep their jobs if the public approves of them! They should know better.

The learning curve for getting reports out of link shorteners is painless. Anyone whose tweets are in service of a larger goal has no excuse not to begin to use these tools in their social media activities.

Give it a shot and see what you learn. When you do, you can feel proud that you’re using the same avant-garde techniques the President’s campaign team is using!

Keep up to date with future updates to this series by following me on Twitter and/or subscribing to updates to this website. To see all posts in this series, visit the overview page.

To move on to Secret #2, click here.

Notes

- Why have a private URL shortener like OFA.BO? One reason is just pure branding. But another reason comes when people re-tweet something from the campaign. No matter whose tweet(s) you look at, if the URL starts with OFA.BO, you know that the URL originated from the Obama campaign and is safe to click. If you see a bit.ly or any other link shortener’s URL, then you really don’t know — is it a link to real campaign content, or is it a link to a spam or phishing site? If you are a large company with a reputation to protect, you should probably invest in your own private URL shortener for the same reason. This cost is negligible. You can even use the same services Obama and Romney use!

- Twitter adds an extra wrinkle to the process of getting to your final URL, but it doesn’t fundamentally change the process. Twitter runs all URLs (even ones already shortened elsewhere) through their t.co link shortener, so your browser actually goes to t.co first. In the case of Obama’s links, t.co will return an ofa.bo URL to the browser. Then the browser goes to ofa.bo and retrieves the YouTube URL. Finally, the browser gets the YouTube page and you see the video. You still probably don’t notice the process of bouncing around, but it is going to be slower than going right to YouTube.

Resources:

- Sign up for a free Bitly account

- Hootsuite, a free-to-paid web-based service for managing social media accounts

- Tweetdeck, Twitter’s free application for scheduling and tracking tweets

Asides:

- The OFA.BO web site is managed by a company called ShortSwitch.

- MI.TT is managed by Bitly.

- OFA stands for “Obama For America”. .BO is the country domain for Bolivia.

- .TT (of MI.TT fame) is for Trinidad and Tobago.

- Either country, if they wanted to annoy a candidate, could cancel the candidate’s domain and leave his URL shortener out of action. That’s not likely to happen, but we can guess that bit.ly was nervous recently since “.ly” is Libya’s top level domain…