If Esquire ever puts Touré on the cover of its magazine, it’s going to need to re-stage its iconic 1968 cover photo of Muhammad Ali. Not in the ironic sense that they’ve done it lately, but in a sincere sense that it’s appropriate. For there are few people who suffer the volume of unrelenting criticism, insult, and anger that is leveled at him on Twitter. That activity tells us a great deal about social media’s nasty side, and is a cautionary tale for anyone who views social media as merely a sort of chatty email.

To get a sense of that nasty side, it’s interesting to do some statistical analysis on the Tweets he receives. Using the last week’s activity on Twitter as a sample, I discovered some interesting things.

First, Touré’s a popular guy. That’s not surprising, but the amount is still impressive: he receives around 1,000 messages on Twitter a typical day1. That’s roughly one tweet a minute, 24/7. That alone is an intimidating volume for any one person to sort through. Periodically, his volume spikes, too, like it did the end of last week (3/24) when various conservative web sites decide to call him out for something he said (or, more the case, they imagine he said) on his show, MSNBC’s The Cycle. These call-outs are a call-to-arms for their readers, such as this recent one from Twitchy:

That these claims are misleading is irrelevant; I’m interested in the reactions it provokes. Although even without a regular goosing by the conservative web, Touré’s timeline is full of messages.

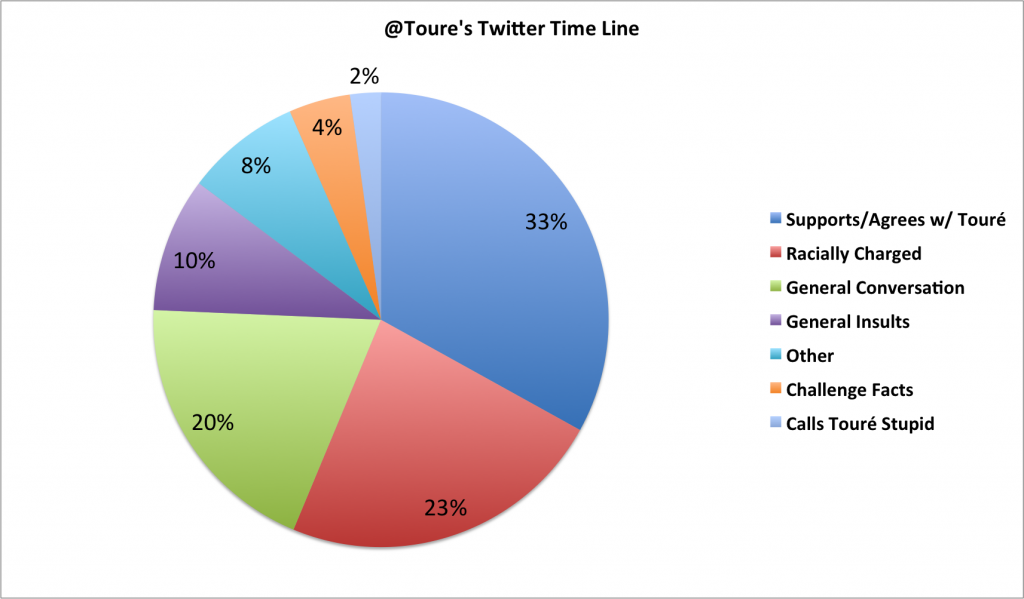

What does everyone have to say to him? Here’s a break down of those tweets:

About a third of the Tweets that land on Touré’s timeline agree with him, support him, or are retweets without comment of something he’s tweeted. A fifth of them are just general conversation. So about a half of them are what I’ll call “nice Tweets”.

Then there’s the not so nice. About a quarter of the Tweets he receives either accuse him of being racist, using racially charged language, or are racist2. Ten percent just insult him in general, and eight percent are kind of snarky. Only four percent of the tweets that disagree with Touré challenge him on facts (without also insulting him personally). Finally, only two percent call him stupid. Touré’s got that going for him, I guess!

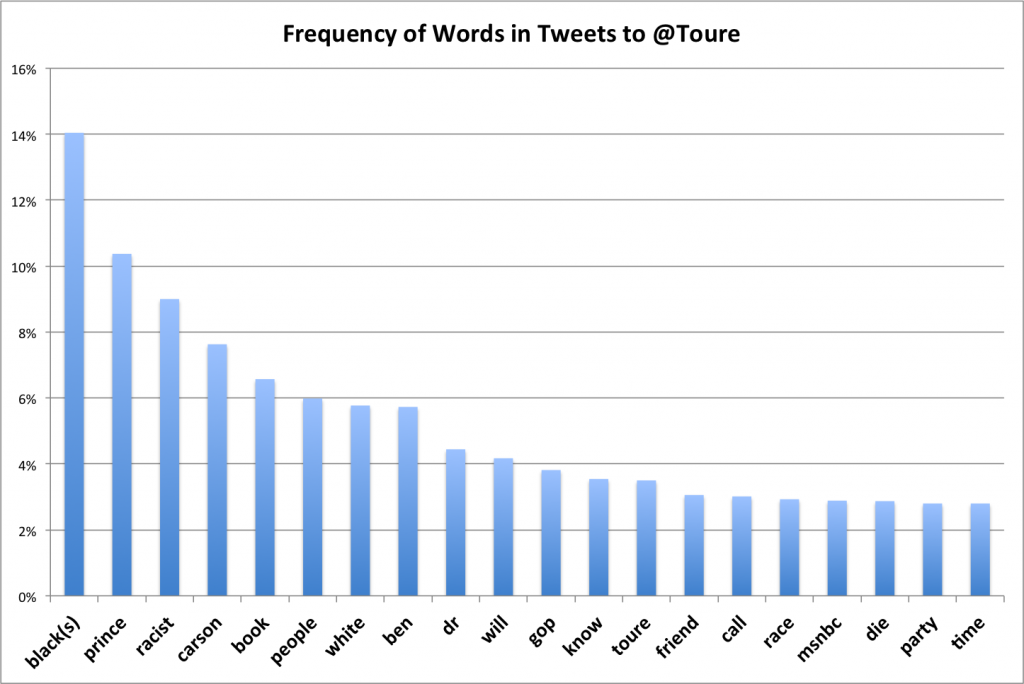

All told, about 50% of the tweets Touré receives are actively hostile to him. That’s got to be a fun timeline to have. What do all these people talk about? Here’s the 20 most popular words (not counting “stopwords”3) that folks have been using recently:

The most popular word in tweets to Touré: Black. No surprise, given that a quarter of the Tweets to him are racially charged, and for the most part the racist folks use a fairly constrained vocabulary. Again, many of the recent Tweets are in reaction to the urgings in the conservative blogs, but on the whole they only amplify the existing long term trends.

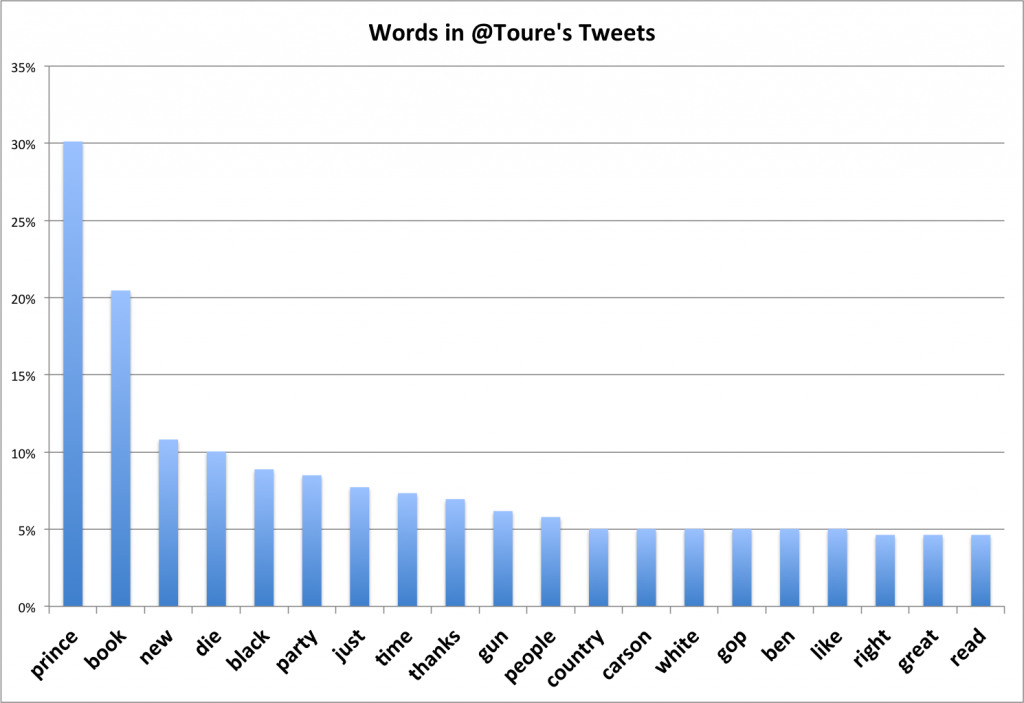

But wait, you say, the high volume of race-oriented tweets are because people are just responding to Touré and the topics that he tweets about! But is that really the case? What words does Touré use in his Tweets? The following shows the frequency of the most popular words in his Tweets from the same period, last week (approximately 250 Tweets sent). Bear in mind that Touré retweets (with comments, usually) frequently, and the words often are not solely his:

About a third of his Tweets are about Prince, which is not surprising, since Prince is the subject of Touré’s just released book. “Black” only shows up 9% of the time. If you take the last three months or so of Touré’s tweets and ignore the retweets and replies (so just his original tweets that are not in response to someone else), he only uses the word “black” about 3% of the time, slightly less often than he used the word “Oscar”.

This means that despite Touré almost never initiating the subject of race on Twitter, race is nonetheless the dominant conversation that people want to have with him. Is it because he is african-american and speaks his mind on race that Touré has become such a lightning rod for (obvious) racists? Why else would they want to find him on Twitter and tell him that they know better than he the true condition of african-americans in this country? Why do they mob him on Twitter with such negative messages when, it seems, he mostly wants to Tweet about his book and sports?

We all know the answer to that question, unfortunately: It is the problem we all still live with.

For anyone looking to be involved in Social Media in a professional way, it is important to understand that Twitter is not just a channel of communication, but at times an echo chamber for the angry psyche of the public. A large mob can be whipped into action by an influential few, and the results can be confusing if you don’t understand what’s happening. Learning how to manage that is a new skill for a new era.

Footnotes:

1 Countless more mention Touré’s name without his Twitter ID, but are impossible to categorize since there is another popular Toure on Twitter. For the Tweets I could categorize, I took a statistically valid sampling of the tweets and assigned them to the categories in the pie chart. The confidence interval is +/- 5% with a confidence level of 95%. Statistics FTW.

2 For example … well, just trust me, it’s really obvious. I’m not going to repeat them.

3 Stopwords are words like “this”, “and”, “is”, etc., that appear in everybody’s text but don’t really tell you anything about the content. Generally speaking, analysis programs will filter them out.