Yesterday, we all awoke to discover the urgent need to change our LinkedIn passwords. A file containing millions of “hashed” passwords was stolen by hackers and then posted on the Internet.

At this point, the real extent of the damage is unclear. The file which was posted contains passwords, but no user names, so it is useless as-is for any nefarious purpose. It was also not a complete list of passwords. Those two omissions leave us wondering what more, if anything, the hackers have: do they have the complete list of all passwords with associated users? Or did they just find something embarrassing to LinkedIn but with no real value to wrongdoers?

Perhaps those questions will be answered over time, but it was clear that everyone needed to change their LinkedIn password immediately. That much is common knowledge.

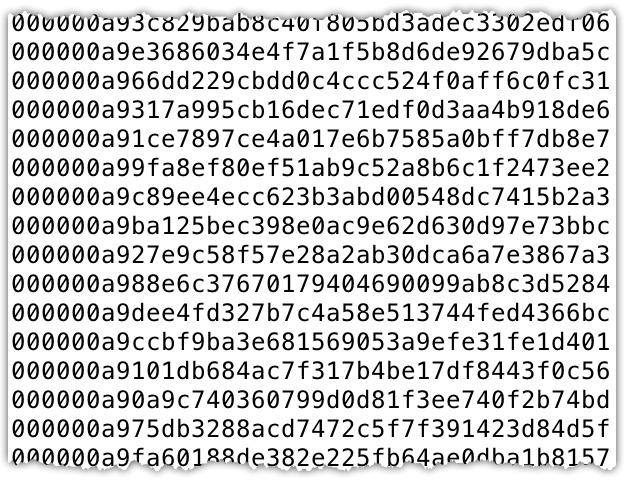

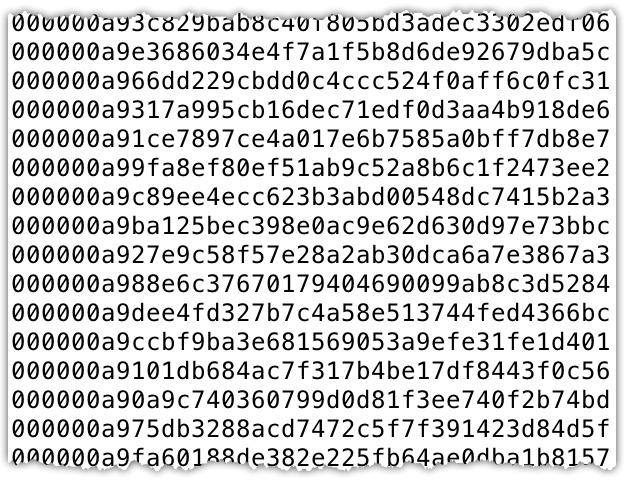

Because the list has “hashed” password (more about that in a minute), it’s not possible to see the actual passwords people used:

But it is nonetheless possible to check to see if a password you know is in the file.

A quick technical diversion: LinkedIn, like most web applications, does not store your actual password on their system. So then, the question is, how can they tell if you’ve entered it correctly? The answer is that they compute a sort of score for your password, called a hash, and store that. If the score they saved of your password matches the score of the password you are entering, they let you in.

For a very simple hash function, consider the following. let’s say you assign every letter of the alphabet a number, starting at 1 for A and ending at 26 for Z. When someone enters a password, you add up the numbers for the letters. A password of ABC gets a score of 1+2+3=6. So they store 6 in their database. Now, if you enter ABD as your password later, the software adds the letters up, and since 1+2+4=7, there’s no match.

Now, imagine you, like the hackers, have stolen this file containing all the scores. Just by knowing the saved password is 6 it doesn’t automatically give you ABC. However — and this is the important part — if you know the score is 6, you can invent a password — for example “EA” — that has the same score (since 5+1=6). If you were to use EA as a password in this (fictional) scenario, LinkedIn would say your password matches and let you in!

The actual formula used is far more sophisticated, and, as you can see by the sample printout of the leaked passwords, the results are far more complicated. But, in theory, the two approaches are exactly the same. And, so, with some effort, if the hackers wanted to break into an account, they could generate a fake password that gets the same score as yours without ever knowing your real password. It doesn’t matter, the fake one will work as well.

As an alternative, the hackers could try a list of common words. Some people have very simple passwords, and a list of words (called a “dictionary attack”) will uncover some significant number of passwords. Some hackers even keep a list of pre-hashed dictionary words around (called a “rainbow table”, in non-obvious naming), so it’s faster for them to check common passwords.

Still, how do you know if your LinkedIn password was in the file — when all you know is your actual password? You will have to score your password (or “hash” it as it is really known) and look for that value in the file. Two big obstacles for most people: figuring out how to compute the hash of their password and then getting a copy of the leaked file to see if your hashed password is in it.

Fortunately, a reputable software vendor who sells password management software (which is a really good idea to use) has built a web site where you can see if your password is in the LinkedIn file. Their web site is at:

https://lastpass.com/linkedin/

Just because your password is not in the file, should you not find it, does not mean you are safe. You should assume the hackers have more than they have given out publicly and that they really do have your hashed password.

Once you’ve checked for your password, you could call it a day and move on.

Or, if you have a strange curiosity like I do, you can see that this password file presents an interesting opportunity for a little research into what people use for passwords.

First, a word about ethics: the file has passwords, but no users. There is no way you can break into someone’s account using this file (but we presume the hackers know more and could break into people’s accounts, so that’s not a reason to be complacent). The passwords are completely anonymous. We have no way of knowing whose passwords these are. Also, the password file is now out in the open, so looking at it does not represent a subsequent unethical hacking.

With that observation, let me point out that when you visit that web site to check your password, you can invent any password you want and see if it was used.

For example, those of you with a political bent will find that “romney” was used by somebody as a password, but “obama” never was. “clinton” was used, but “bush” wasn’t. There’s nothing you can really conclude from that, however. This is just password voyeurism.

Where it does show some insights into humanity, perhaps, is when you try out phrases that are more personal nature. Just about anything you can think of (or, I should be more precise, anything I can think of — perhaps my horizons are not broad enough) is in there as a password. On the plus side, there are plenty of inspiring religious terms I found. “jesussaves” and “john316” (Tebow? That you?). That makes me feel some faith in humanity. On the minus side, well, I don’t want to repeat some of the more salacious passwords I tried, but HL Mencken was right. Whatever level of depravity I have, LinkedIn users showed me I’m just an amateur. I’m pretty sure that I’m out of my depth here and that my imagination pales in comparison to the collective perversity of 6.5 million people.

So give it a whirl if you like. It’s a kind of “hot or not” of passwords. Again, I want to point out the ethics of this are pretty clear — you are not hacking anyone’s account by doing this. You are not decrypting everyone’s passwords. You are not discovering something private about a person. You are just looking at anonymous information and seeing if passwords you can concoct have been used.

If you can draw any conclusions from the password file, it is only that a lot of people hate their passwords. And, yes, somebody used “ihatepasswords” a password.